[Credit: Daniel Cohen, Erykah Badu, 2008]

Currently running at The Photographers’ Gallery in London is an exhibition titled We Want More: Image Making and Music in the 21st Century, which displays various forms of modern music photography with the aim of highlighting the differing ways in which music-related imagery is produced and consumed. The curator of the exhibition – Deputy Editor of the British Journal of Photography, Diane Smyth – was kind enough to answer a few questions that we sent her, and gave us some more information about the exhibition and her take on some of the themes highlighted by it.

Additionally, on the 14th of September as part of the exhibition a panel discussion will take place entitled Girls Rule The World, discussing female imagery in the music industry and whether or not women can be said to be in control of how they are presented. Panellists will include cultural commentator Ekow Eshun, Little Boots and Juliette Larthe (music video producer for Rihanna, M.I.A and others), amongst others. More information and tickets available here.

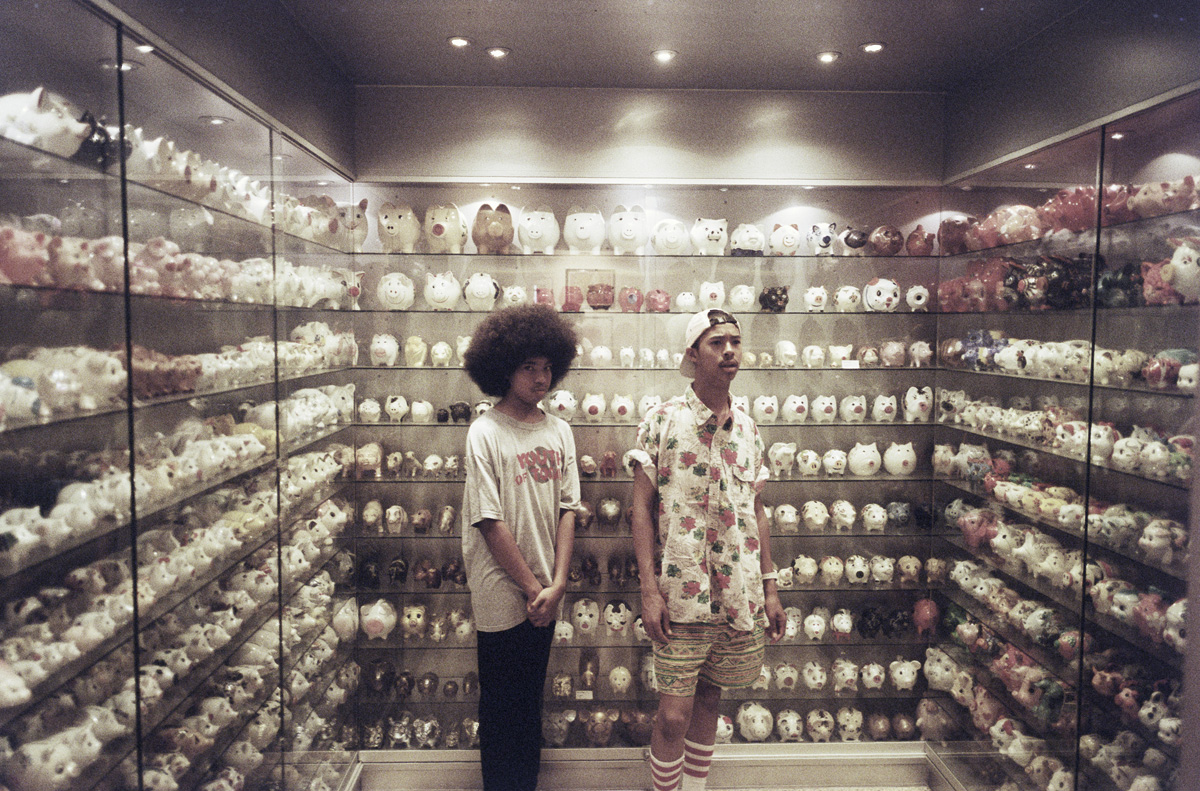

[Credit: Deirdre O’Callaghan, Pauli The PSM, 2014]

Hello Diane, for anyone who hasn’t heard about it, could you please give us an overview of what We Want More is all about and what you’re trying to show with the exhibition?

It’s an exhibition about music photography, but I’ve deliberately made it a show looking at contemporary music photography, e.g. shot since the turn of the century. That quite naturally lead me into thinking about the way that music photography is initiated and distributed, be it commissioned from the music label for online dissemination or started as a personal project by the photographer and self-published as a zine. I wanted to focus on work by people who make a living out of photography rather than amateurs who, for example, like to photograph gigs they attend, as I wanted to take a look at how the music industry uses photography, though not all of the projects were commissioned. All of them have a link with the music industry in some way though – when it comes to photographing musicians, I think you probably have to be involved with the industry in order to get any kind of access at all.

I also found that they very much focused on portraits of the people involved, which I guess may be the nature of the beast when it comes to showing off the musicians involved in the scene. But I also found a lot of nice projects focusing on fans, rather than musicians, and so I ended up making an exhibition of two halves – one floor showing pictures of musicians, the other floor showing pictures of fans. Some of the fans have adopted the image of the musician whose music they like, which I found really interesting, as it shows the power of the image that that musician has cultivated and publicised.

[Credit: Pep Bonet, Motorhead, 2008]

You’ve spoken in a previous interview about the shift from music photography being mainly shown in printed magazines to a lot of it being distributed online. Do you think the changing nature of the distribution channels has changed the photos themselves? William Coutts’ images for Noisey that you have in the exhibition, for example, are quite unique.

Yes, definitely – and the William Coutts images are an interesting example. They show people in the crowd at a gig which was organised by Noisey, Vice’s music channel, and were published on Vice’s music channel. It shows people moshing and generally lost in the spirit of the night, which you could say is a good way for Vice to advertise its gig e.g. to show what a great time people will have by going. I think it also allows the magazine to strike a certain tone with their readers, to come across as being quite on a level with them. But also, and this is really interesting, Vice’s UK picture editor told the British Journal of Photography recently that the magazine actively seeks out shots of the scene around music, rather than just the musicians, as the internet is so flooded with the official portraits of the stars. So yes, the fact that the internet exists has encouraged that particular magazine to take a different approach to shooting music.

The exhibition is a mixture of commissioned photography and personal work. As high quality cameras have become cheaper and the internet has enabled everyone to get their photos seen by a large audience, do you think personal music photography is more important now than ever before?

I think that in general photographers have more opportunities to show their personal work now – so where a music photographer might only have been able to publish commissioned photography in magazines, they can now choose to make a personal project about some aspect of music and show it in an art gallery, or publish it as a book. That’s also changed the kind of images that photographers shoot (or at least that I know about) as whereas before they might have needed to focus on images of musicians that would be good to publish in, say, a music magazine, and that might therefore tend to be quite flattering, now they can publish images showing the stars looking tired after the show, or show the fans instead. I also think though that the prevalence of cameras and means of distributing photographs has had an effect – if anyone in the crowd can now photograph a gig, what does a professional photographer add by doing so? I think magazines such as The Wire have been quite canny in that they focus on behind-the-scenes shots of musicians, the kind of privileged access that the ordinary member of the public wielding a camera phone can’t get. Also, I think that the prevalence of images online means that stars such as, for example, Lady Gaga, need to do more to grab attention – by, for example, creating grotesque or shocking images, designed to stop the viewer in their tracks and get shares.

[Credit: Dan Wilton, 2012]

Do you think that music photography conversely impacts the music itself? As in, are visual aesthetics and aural aesthetics mutually constitutive?

It’s an interesting question. I think it’s strange in a way that music and imagery are linked, as music is aural not visual! But they have had a long history, partly to do with trying to shift units e.g. using photography on records or in the press to help publicise them. I guess it might be down to the individual musician and fan involved? For example, I can definitely think of albums I enjoyed listening to, whose album art I really enjoyed too, and which added something to the overall experience. I can also think of some contemporary stars whose image is really out there but whose music I find really bland!

Alongside the exhibition you have a series of events running discussing ‘the visual aesthetics of underground and experimental music scenes’. This is an interesting contrast to some of the more ‘mainstream’ music photography out there. Is modern underground music something you are interested in? And how do you think the visual aesthetics of these types of music contribute to its overall presentation?

I actually didn’t organise the events, though I think the team at The Photographers’ Gallery did a great job with that. To answer your question re: mainstream vs underground aesthetics though, it’s definitely very interesting – though also hard to generalise. For example I’ve included some shots Jason Evans took of Radiohead in the show, in which the band subverted the usual pop star iconography by deliberately looking as everyday as possible. On the one hand maybe you could say that that rejection of the usual publicity machine shows how alternative they are – but on the other hand, those images were shot when they were at the height of their fame, one of the biggest bands in the world, and partly able to reject the publicity machine because they were so big that their record label wasn’t about to object. Also there are underground stars who adopt very carefully controlled images – there’s a video of FKA Twigs in the exhibition, for example, who’s an emerging artists but who has a very interesting, very carefully crafted, and still glamorous image. It’s difficult to generalise I’d say.

Another interesting event that runs alongside the exhibition is a discussion on 17th September around the title ‘Girls Rule The World: Visual Pleasure, Sexual Politics and Image Control’. Do you think music photography can be an empowering tool for female artists, or whether the nature of the ownership and distribution of the images (often outside of their control) means that it can be a mode of objectification and disempowerment?

It’s a really big question and I’m sure it will be a really interesting discussion. It’s definitely interesting to see how female musicians are presented, or present themselves, in music photography – I love the PJ Harvey video in the exhibition for example, and the fact that she just practices her song in her kitchen, allowing it to be seen when she makes mistakes. I feel that in that video, the image presented is of a musician at work, rather than a star (which she is) presenting a vision of glamour… It’s also really interesting to see contemporary female artists adopting grotesque images such as the images of Lady Gaga in the show by Inez van Lamsweerde and Vindoodh Matadin, or the gifs of Katy Perry, or the way that Yolanda Visser from the group Die Antwoord is portrayed in the images I’ve included of her by Roger Ballen – though I think, for example, Lady Gaga and Yolanda are still pretty obviously very attractive young women. Maybe the answer depends a bit on your take on Third Wave feminism?? EG on whether you think that adopting the traditional trappings of femininity that previous waves rejected can be empowering? Re the images being out of their control though, I think that’s always the case with photography, and that’s one of the things that’s interesting about it. One an image is out there, the viewer can see it how he or she chooses; also in this show I’m deliberately re-contextualising music photography by putting it in a gallery and therefore putting it under a different kind of scrutiny to the kind of scrutiny it might have on, for example, an online slideshow.